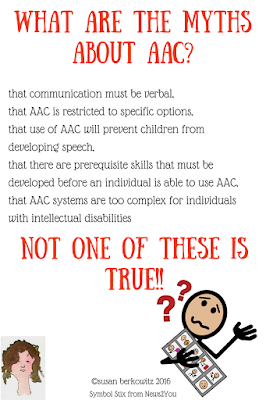

The myths of AAC are a combination of misconceptions and misinformation. Unfortunately, they are both pervasive and dangerous.

They may continue to be perpetuated by beliefs

- that communication must be verbal

- that AAC is restricted to specific options

- that use of AAC will prevent children from developing speech

- that there are prerequisite skills that must be developed before an individual is able to use AAC

- that AAC systems are too complex for individuals with intellectual disabilities

Not too long ago I got a call from a mother. She was interested in looking into AAC for her child, but the school district said the child was too young. How old was he? He was 6.

Last week I had the same experience. This time, however, the child was 3. As soon as I put a dynamic display device in front of her with core words to use in our play interactions she began to use the system independently to direct my actions and her choice of activities, including which colors of markers she wanted.

Too soon for AAC?

Two years ago I attended an IEP meeting for a girl for whom I was providing consultation. The school district was appalled when I suggested an AAC system as a repair strategy. She was verbal; but with a repertoire of less than 3 dozen words. Their response; “We’re not giving up on speech. It’s too soon!” How old was she? She was 9.

And note that I suggested an AAC system as a repair strategy, not as a replacement for speech.**

BUSTING THE MYTHS:

Some parents and professionals believe that AAC is a last resort for their nonverbal or minimally verbal children, and should only be used when there is no more hope for developing speech.

Unfortunately, this all too often means that children (and some adults) have no means of communicating for far too long; resulting in frustration, negative behaviors, and significant limitations on their language development, access to curriculum in school, access to social interactions at home and in the community, and in adapted living skills.

Waiting too long to provide a mode of communication denies the child the opportunity to learn language, acquire vocabulary, and express himself appropriately. Waiting too long to provide an appropriate mode too often means communicating with an inappropriate mode. Research shows that any intervention delayed beyond a child’s first three years has less significant impact, and that children - including those with disabilities - learn faster and more easily when they are young. Lack of access to communication results in the individual being excluded from appropriate educational and vocational placements, restricting social development and quality of life.

Rather than being a last resort, AAC can serve as an important tool for language development and should be implemented as a preventative strategy - before communication failure occurs. Withholding AAC intervention not only impacts building language skills, but also has an impact upon cognitive, play, social, and literacy skills development.

BUSTING THE MYTHS:

Parents and professionals may also believe that use of AAC will stifle the child’s potential verbal skills and/or serve as a “crutch” upon which the child will become reliant. However, research has shown that use of AAC often stimulates verbal skills in users with the potential to be at least partially verbal.

Children need access to appropriate and effective modes of communication as soon as possible. Without an appropriate way to communicate genuine messages, individuals frequently use inappropriate behaviors to communicate, or withdraw. Struggling to learn to speak, while having no other way to communicate, leads usually to frustration.

Further, those who have access to AAC tend to increase their verbal skills. So, not only is there no evidence to suggest that AAC use hinders speech development, there is evidence that suggests access to AAC has a positive impact on speech development.

Why AAC use promotes speech development is not precisely known. Theories include the possibility that use of AAC reduces the physical and social/emotional demands of speech and that the symbols/words provided visually serve as consistent cues and the speech output provides consistent models. Although the goal of AAC intervention is not necessarily to promote speech production, the effect appears to be that it is a result.

BUSTING THE MYTHS:

Many times parents are told children need to have a set of prerequisite skills in order to qualify for or benefit from AAC, and that their young and/or severely disabled children (and adults) do not yet possess those skills.

In addition, some professionals believe that there is a hierarchy of AAC systems that each individual needs to move through; utilizing no- or low-technology strategies before gaining access to high technology systems.

In fact, this outlook only tends to limit the type of supports provided and limit the extent to which language may be developed.

First, there are NO prerequisites for communication; everyone does it. And as we’ve seen above, all children learn to communicate before learning to speak.

Second, research does not support the idea of a hierarchy of AAC systems, and shows that very young children can learn to use signs and symbols before they learn to talk. Research has also shown that very young children with complex communication needs have learned to use abstract symbols, photographs, and voice output devices during play and reading activities.

Requiring an individual to learn multiple symbol systems or AAC systems as they develop skills merely serves to make learning to communicate more difficult.

BUSTING THE MYTHS:

Many parents and professionals believe that AAC is only for individuals who are completely nonverbal. Students who have some speech skills are frequently not provided access to AAC systems in the belief that intervention should focus only on building their verbal skills.

However, if speech is not functional to meet all of the individual’s communication needs - that is, if the student does not have sufficient vocabulary, is not understood in all environments, or if speech is only echolalic or perseverative - AAC should be considered.

“Any child whose speech is not effective to meet all communication needs or who does not have speech is a candidate for AAC. Any child whose language comprehension skills are being claimed to be ‘insufficient to warrant’ AAC training is a candidate for aided language stimulation and AAC.” (Porter, G.)

BUSTING THE MYTHS:

When working with individuals with severe disabilities - particularly intellectual disabilities - many professionals assume the individual is too cognitively impaired to use AAC.

Kangas and Lloyd (1988) wrote that there is no “sufficient data to support the view” that these individuals cannot benefit from AAC because they have difficulty paying attention, understanding cause and effect, don’t appear to want to communicate, are unable to acquire skills that demonstrate comprehension of language, are too intellectually impaired.

The relationship between cognition and language is neither linear nor one of cause and effect; they are correlative. They are intertwined in a very complex way. We cannot say that a specific level of cognition or skills needs to happen before language develops. They are interdependent. We often see language skills in the (supposed) absence of expected cognitive skills.

Research and observation continue to indicate that there is no benefit to denying access to AAC to individuals with significant disabilities. Intervention should be based on the idea that learning is based on the strengthening of neural connections through experiences and that repetition of these connections through multiple modes facilitates learning. Providing users with rich experiences with their AAC systems builds on the neural patterns and facilitates communication skills building. Not providing AAC services based on preconceived ideas about the cognitive skills of the individuals simply continues to segregate and limit access to life experiences for them.

BUSTING THE MYTHS:

Unfortunately, there are also those who believe that simply providing access to an AAC system will solve the communication problems of the user.

The AAC system cannot “fix” the individual or their communication difficulties. While use of AAC will facilitate development of speech or language, and of literacy skills, and will increase the individuals’ ability to communicate effectively, it will not do so simply by being there.

The AAC system is a tool and, like any tool, the user needs to know how to use it. And for most of those individuals, direct, specific, and structured intervention and opportunities need to be provided.

Users and their partners need to accept the AAC system; they also need appropriate instruction in how to use the system and how to develop effective communication and further language skills with the system.

The success of the AAC system is not dependent upon only the individual’s skills and cognitive abilities. It is also not only dependent upon the completeness or robustness of the AAC system. It is strongly dependent upon the willingness, training, and responsiveness of partners. Partners who do not understand the need for the AAC system are less likely to respond to the individual’s communication attempt with it. If the partners have low expectations of the AAC learner, do not respond consistently, do not use aided input consistently or do not provide sufficient communication opportunities the AAC learner is not likely to progress. Communication partners have a significant responsibility.

I know this has been a really long post! But I hope it proves you with some good information with which to arm yourself.

Here is a free handout you can download.

Here is a free handout you can download.

Until next time, Keep on Talking!

No comments

Post a Comment